Vue user-permissions through directives

Michael Bøcker-Larsen • November 3, 2017

vue howtoThis guide is a post-mortem on my experiences from writing vue-browser-acl, a standalone Vue.js component that brings ACL (Access Control Layer) to the browser in the form of an easily comprehensive directive.

At the end of this article, we will end up with Vue directive that looks something like this:

<button v-can:delete="post">Delete</button>

We will cover these topics:

- Directive arguments and modifiers

- A directive’s lifecycle

This is not an article about ACL best practice, but a guide to how you can make your code more readable and pleasant to work with for others and your future self.

Motivation

Vue provides you with v-if and v-show out of the box and I’m sure your templates, like mine, are littered with these two directives.

They are the equivalent of the if-else control structure we know from our code and, not surprisingly, we often end up having long and deep conditions that force you to stop in order to read them to understand.

<button v-if="job.users.contains(user) && user.isManager()">Delete</button>

Often in Vue you would extract these into computed properties or a component method to hide away the complexity:

export default { methods: { canDelete(job) { return

this.job.users.contains(this.user) && this.user.isManager() } } }

This lets us simplify the button’s condition:

<button v-if="canDelete(job)">Delete</button>

However, this doesn’t scale well. You will have to duplicate this or similar code to all of your components whenever you want to check the user’s permissions for a certain action or view.

Mix-ins are a great way to leverage code duplication. You can also extend the vue prototype like we’ve done for years in JavaScript. (I’ll refer to both approaches as mix-ins for simplicity). Mix-ins allow us to consolidate all the access code in one place and make it available from all Vue components. For example, we could add a $can mix-in (in fact, we will do that later) and now transform the button to something like this:

<button v-if="$can('delete', job)">Delete</button>

Although mix-ins are vastly better and for most parts get the job done, I believe that we can do better with directives.

ACL Primer

First, I’ll briefly cover our requirements. ACL in the browser is mostly there for UX purposes and is no replacement for checking permissions in the backend.

There are many approaches to ACL. There are different granularities and ways of expressing permissions, but it basically boils down to defining how a user, possibly through a role, can perform certain actions (or verbs) on the models in your application. The actions can be anything really: create, view, edit, delete, transfer, send, manage members, etc.

The library we are using is kind of agnostic about users and roles as long as you pass in something your rules can make sense of.

As to the models in your app, there is distinction between classes and instances. When you have an instance of something, say a post, and you want to determine if an edit button should be enabled, you would likely check if the current user is the owner of the post.

acl.rule('edit', Post, (user, post) => user.id === post.userId)

The point is that for the verb edit we will need an instance of a post to determine the permission.

For a verb like create, on the other hand, we won’t be able to provide an instance since the post doesn’t exist yet. But we will have to pass something for the ACL to be able to determine if the user should be able to create a post:

acl.rule("create", Post, (user) => user.isRegistered())

So in this case, we can either pass the class of Post or a string ‘Post’ instead of an actual instance.

In the example above, the create action can only be performed in case the user is registered. An important point is that the Post argument is only used to tell that the rule is about posts and it is not used in the code that determines the permission; only the user is.

This is not terribly important, but it will guide us in some of the choices we’ll make when designing the v-can directive going forward.

Vue.use()

Directives and mix-ins alike are plugged into Vue by calling use(plugin). It expects an object with a method called install. Vue calls the method and includes itself as the first argument. And each argument you pass to use after that will be passed to install as well. (see plugins section)

Vue.use({

install(Vue, options, moreOptions, evenMoreOptions) {

...

}

})

Defining rules (options)

For this particular directive, the plugin user will need to:

- Provide access to the current user

- Define some rules which are the base for the ACL to work

There are several ways to provide these.

You can set up all rules and configurations on an object and then pass it ready with rules and all to Vue like so:Vue.use(instance). This is what vue-router does.

You can also simply pass in the plugin and then do all the configuration in the install function. However, we want to hide away the “mess” of importing and creating an Acl instance, but we still need to expose this instance so that the plugin user can add rules to it.

It could look something like this:

import Acl from "vue-browser-acl"

Vue.use(Acl, user, (acl) => {

acl.rule("edit", "Post", (user, post) => user.id === post.userId)

})

First, we pass our plugin Acl (remember a plugin is just an object with an install function) and secondly, we pass the user. There are no requirements as to what a user is. It can be an email, an object, a role, or even null. We will use this later to pass to the Acl’s can() function.

The third parameter is a callback that provides the acl instance (code we still have to write) as the first and only parameter.

Using a callback is a way to expose what is relevant to configure the plugin, and hide away everything else.

In the above code, we define a single rule — a rule for checking if a user may edit a post or not.

Before starting on the directive, we will add the mix-in or helper function that is still useful for cases where you cannot use the directive. See a few examples in the the released package.

Let’s look at our plugin and how we can provide the proposed API.

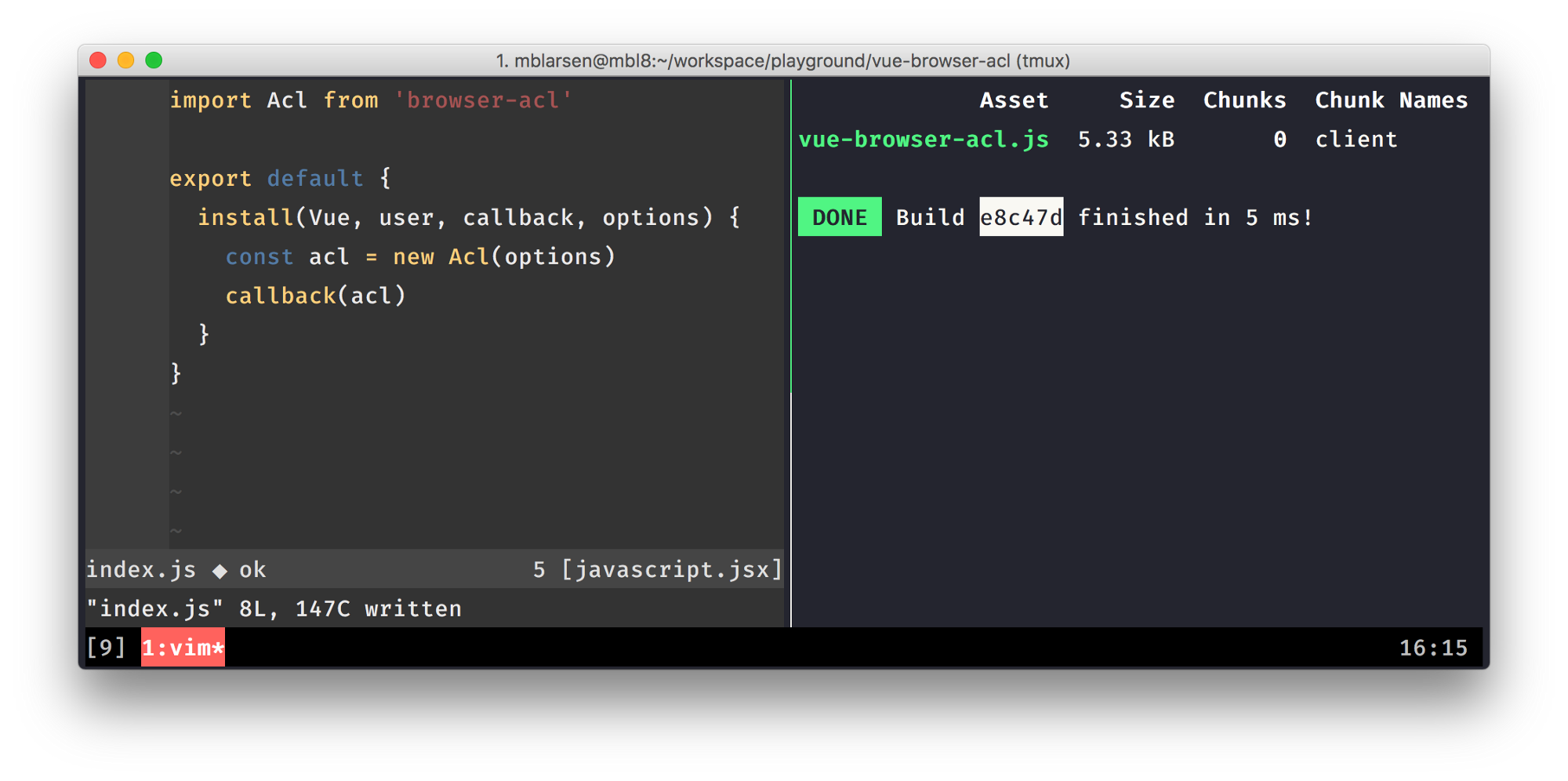

import Acl from 'browser-acl'

export default {

install: function (Vue, user, callback, options) {

const acl = new Acl(options) callback(acl)

}

}

That is really all it takes. Note that I’ve added the option for a third argument in case you want to pass options to the underlying ACL module.

I use poi to build and bundle the package. Poi lets you use all the features of Webpack without having to configure anything.

I use poi to build and bundle the package. Poi lets you use all the features of Webpack without having to configure anything.

Helper Function

Our ACL is now hooked up but we are still unable to do anything with it. Let’s add the helper function before starting on the directive.

import Acl from "browser-acl"

export default {

install: function(Vue, user, callback, options) {

const acl = new Acl(options)

callback(acl)

Vue.prototype.$can = (...args) => acl.can(user, ...args)

},

}

Adding a helping function is easy. We add a function $can to the Vue.prototype after which all Vue instances can access the helper function. That means we make use of the function already:

<button v-if="$can('edit', post)">Edit</button>

It is important to point out that post must exist as data (or computed value) on the component or must reference a variable in a loop (v-for="post in posts").

Now that the ACL functionality is in place, it is time to create the directive.

Directives 101

The documentation for directives is pretty good, so I won’t go into much detail, but I will only cover the the parts that are relative to our can-directive and likely for most directives you’ll ever write yourself.

This was the example we started out with — accompanied with a few other familiar “faces”:

<button v-can:delete="post">Delete</button>

<input v-on:keyup.enter.prevent="validate" />

<a class="btn btn-link" @click.prevent="save">Save</a>

To break it down further into detail, the directives above are:

v-can with an argument delete and an the value expression post.

v-on with an argument keyup and a modifiers enter and prevent.

@click is syntactic sugar for v-on:click but, as such, acts as a directive with a modifier prevent.

The name of a directive is the name without the v- and this is how you register them: can, on

A directive can have a single argument that always comes after the directive name. For v-on the argument is used to specify which event to listen on: keyup, click, to name a few.

A directive can have multiple modifiers. Modifiers are like flags, boolean values, that your directive can react upon. For v-on, modifiers like prevent and stop are used to invokepreventDefault and stopProrogation respectively on the event when fired.

Modifiers can also be used as passing additional arguments. Although this is not the intended usage, this is clearly an accepted practice as seen from the above example in the case of enter. Modifiers will be available as an object with the value true like {enter: true, prevent: true}. Since they are converted into an object with the modifier names as keys, there are limits to how you can use modifiers as extra arguments:

- There is no guarantee of the order

- You cannot have repeated values

So if, for example, we were making a media query directive and wanted to use modifiers for arguments:

<div v-mq.min.764.max.1024>Content only shown for medium devices</div>

This would not work since we wouldn’t know if min or max is referring to 764 or 1024. You would have to device some clever logic to make it work at least.

v-can

(well can we?)

With that out of the way, let’s define the requirements for our directive. We will need to pass in at least two arguments: the verb and an object to check if the user can perform the action on it.

Often, you don’t want to hide an element like a button but you may just want to disable it. In UX land, this translates to telling the user that an action exists but currently, for some reason, you cannot perform it.

So for the directive, we have to figure out a syntax that covers the following: verb , object , hide option (the default) and an option to disable.

We could wrap all this up in an a object and pass it as the value to the directive, but we want to make use of directive arguments and modifiers of course.

hide and disable are mutually exclusive so there can only ever be one value which makes a good candidate for the argument: v-can:hide or v-can:disable.

However, recalling v-on:keyup, it seems that the argument is complementing the name of the directive to describe an event “on keyup”. It nicely describes what the directive does: a binding for what happens when the key is released.

Returning to v-can:hide we get “can hide” which is really not what our directive is about. We want it to read what the user can do, or rather what the user must be able to do in order for the element to be shown or enabled.

Verbs, too, for the most part, are singular arguments. For posts, the verbs could be: create, edit, delete, and comment. These verbs would translate into usage like v-can:create, v-can:edit, and so on. This reads really well: “can create” and “can edit”. There is no doubt what the directive is about.

That leaves hide and disable as well as the object (a post). For the object, we don’t have an option really; it has to be the value.

As we’ve already departed from the idea of providing arguments as a value object, that means hide and disable will have to be modifiers. Which isn’t so bad really. “should hide” or “should disable” are boolean values. Perfect.

That leaves us with:

<button v-can:edit.disable="post">Edit</button>

- The verb is the argument

- Hide/disable are mutually exclusive modifiers

- The object is the value expression

Note: The published package supports other flavors that in some cases make more sense — e.g. you can write v-can="'create Post'" and there is an option to pass verb, object and additional arguments to the rules using an array notation. In addition, it has modifiers that work on a collection of objects.

Implementation

We add directives using Vue.directive(). It takes as the first argument the name of the argument without the v- prefix. So in our case, just can.

The second argument can either be an update function or an object detailing the directive’s lifecycle hooks for greater control. We will implement this using an update function but we will cover the second option in the directive’s lifecycle section below.

The function will be called initially when the containing element is created and will be called subsequently when data changes. It takes three arguments function (el, binding, vnode) of which bindings is the most interesting to us. el is the DOM element and vnode is Vue’s virtual dom node (you can access data properties from there).

The binding argument gives you access to the argument, modifiers, the value and so on.

name: The name without thev-prefixvalue: The value after evaluating the expression (you can also get the expression itself)arg: The argumentmodifiers: An object with the modifier name for key and true for value

For a complete list of binding properties, see the docs.

...

Vue.directive('can', function (el, bindings, vnode) {

const behaviour = binding.modifiers.disable ? 'disable' : 'hide'

const ok = acl.can(user, binding.arg, binding.value)

if (!ok) {

if (behaviour === 'hide') {

commentNode(el, vnode)

} else if (behaviour === 'disable') {

el.disabled = true

}

}

})

...

Default to hide: First, we check to see if the disable modifier is there. If not, then default to hide, in the same wayv-if works.

Next, check if we have permission to perform the action. The acl is in scope since we are still inside the install function of our plugin.

In the event the user is not authorized, e.g. to edit a post, then we deal with the element accordingly. In the event the user is authorized, we do nothing.

The easy case is disable. We turn on the disabled property of the element. That is the equivalent of:

<button disabled>Edit</button>

For hide it is a bit more complicated. The basic idea is that you replace the content with an empty comment <!-- —->. You can see the code here.

That’s it. This is the implementation of the directive.

We have completed our directive which lets us write more succinct templates using v-can. There are many ways to improve on the implementation, but this is the gist of it.

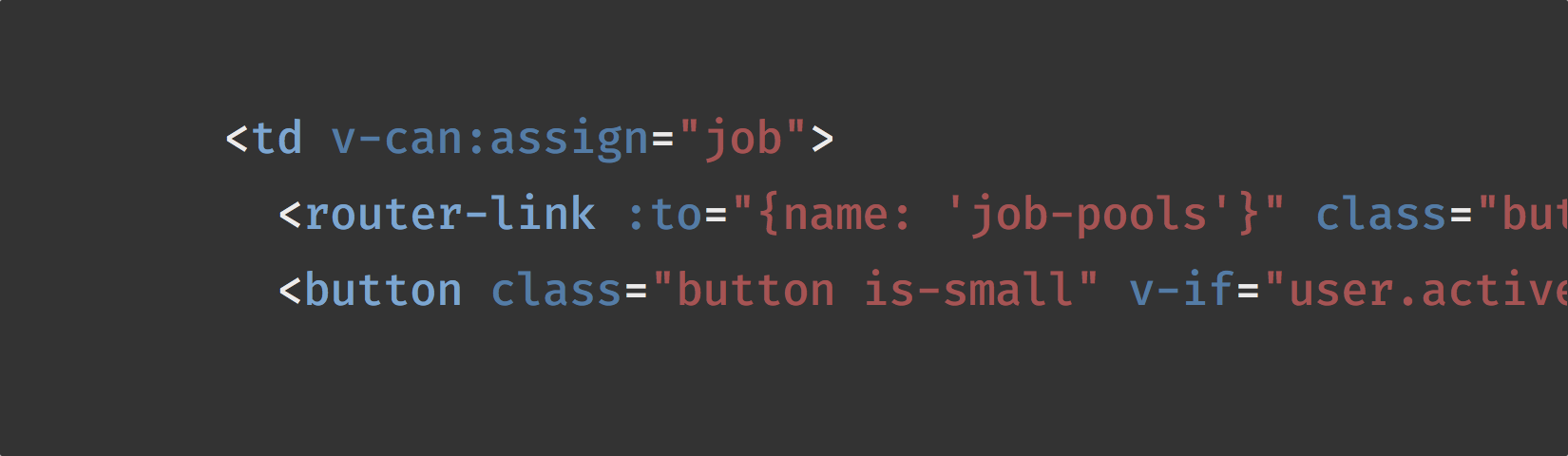

An example of the v-can directive in production (“can assign job”).

An example of the v-can directive in production (“can assign job”).

Directive Lifecycle

I left this bit for the last, in order to add a few more words on what happens when we provide the update function.

Just like a Vue component has lifecycle hooks (created, mounted, before*, etc.) so do directives. However, for most directives, you’ll only ever use two of them: bind and update. Think of them as analogous to mounted and beforeUpdate for components respectively.

In many cases, you may want the same behavior on

bindandupdate, but don’t care about the other hooks.

For that reason, Vue provides a function shorthand which is what we used in our implementation. This assigns the update function to both hooks.

Vue.directive("can", canImplementation)

is equivalent to:

Vue.directive("can", { bind: ourImplementation, update: ourImplementation })

Bind happens once when the directive has been associated with an element (el) after which, it is never called again.

Update happens as data changes through the reactiveness of Vue — from user input or some side-effect. For the v-can, the object of our ACL is what can change. So say the post bound to the component changes to a different post, then the ACL re-evaluates the user’s permissions.

Note: The update hook takes a fourth argument oldVnode and the bindings object also includes bindings.oldValue. This lets you compare the old and new values to avoid doing unnecessary computations.

The other hooks are: componentUpdated, insert and unbind.

Unbind is similar to beforeUnmount and beforeDestroy. It lets you properly tear down whatever objects you have created. Say for instance you are making a directive that will play a sound on hover. Before the component (and thus the directive as well) is disposed off, you would need to stop the audio from playing. Otherwise, it would keep living in the browser, taking up a hardware audio channel.

See the Vue documentation for insert and componentUpdated.

What’s next?

As an exercise for you, try to see if you can implement the string flavor so that you can write: v-can="'edit post'" or v-can="'create Post'" for instances and classes respectively.

Hint: you might need vnode.context

This was an exercise for me in sharing my experiences developing this Vue directive. Questions and feedback are most welcome.

If you got this far, thank you for your attention :)

P.S. Do check out poi and poi-preset-karma which let you develop and unit test Vue components with zero config.